The Differences Between China and Hong Kong

What are the significant differences between how the mainland Chinese view the people of Hong Kong? How do the mainlanders view the local Hong Kongers? Are the locals dissatisfied with Beijing’s attempts to manipulate their feelings? What is the biggest reason why people in Hong Kong distrust protests? These are some of the questions I tried to answer in this article. Read on for more information. But what about Hong Kong’s isolation from the mainland?

Hong Kong’s isolation from mainland Chinese people

Several recent outbreaks of omicron poienivirus in Hong Kong have brought the territory’s isolation from mainland China to the forefront of global headlines. In a current epidemic, elderly Hong Kong residents have died after not receiving two doses of the coronavirus vaccine. The latest virus outbreak has left mainland Chinese Internet users furious, blaming Hong Kong for the recent spike in infections.

Since Xi’s order, the Lam administration has sent 36 news releases to express gratitude to the central Government. But the people of Hong Kong are still not convinced by the Government’s efforts, which have resulted in an unprecedented influx of mainland medical workers. Eggs and bread were nowhere to be found, and only one grocery store on the island’s eastern side was empty of supplies. China has dispatched 30 butchers to restore reserves in slaughterhouses.

In the meantime, Hong Kong is gaining popularity as a financial and tech hub, with almost seven million people living in the city’s sprawling highrise apartment blocks and sharing lifts. The population of Hong Kong is 7.4 million, and most live in tightly packed highrise apartment blocks where charges are shared. Last week, the city opened its fourth community isolation facility to house the sick. This facility is slated to house more than a thousand people. More than 90,000 isolation units are planned in conjunction with mainland authorities and are expected to be completed in a few months.

Since the protests over the law began in 2019, Beijing has increased its control over the territory. While Hong Kong’s legal system is supposed to be distinct from mainland China, Beijing has imposed draconian security laws and jailed or exiled pro-democracy leaders. The isolation between Hong Kong and mainland China has only increased in recent years. It’s no surprise that protests are now at an all-time high.

While Beijing is working to limit the rights of Hong Kong citizens, it’s also attempting to undermine the island’s free-wheeling status. In 2021, Beijing overhauled Hong Kong’s electoral system to allow pro-Beijing candidates to run for the chief executive officer. This signifies that Beijing is trying to close the gap between Hong Kong and mainland Chinese citizens. Meanwhile, Beijing is removing the last vestiges of the «one country, two systems» concept by limiting Hong Kong’s autonomy.

Differences between mainland Chinese and local Hong Kongers

Regarding language, there are many similarities and differences between mainland Chinese and local Hong Kongers. In China, the official language is Mandarin, with Beijing dialect, while in Hong Kong, «Chinese» means Cantonese. However, most written documents are written in the formal style of Hong Kong. Regardless of language preference, it is common for Mandarin speakers to understand Cantonese-speaking people.

Both mainlanders and local Hong Kongers respect authority, but Hongkongers tend to be more concerned with individual rights. The two sides have different work cultures and attitudes toward individual rights. The former has a more pragmatic approach to economic success and is more concerned with the bottom line. Both sides fear the mainland station. As a result, Hong Kong feels more «china-lite,» and the locals fear this is affecting their work culture.

Mainland newspapers often feature national news, but the local media focus more on drama. Mainland newspapers devote more stories to national stories than do Hong Kong papers, and they also tend to use photographs more often. Local reports also place more emphasis on accounts that have dramatic potentials, such as protests or accidents. However, the political nature of both types of press differs. For example, the Hong Kong press often covers stories that involve political dissent.

As a result, local Hong Kongers are often incensed and resentful that mainland Chinese continue to dominate Hong Kong politics. This lack of autonomy is a common theme among Hong Kongers, and their frustration with mainland Chinese meddling has led them to stage months-long protests. They have called for the bill to be repealed, and a police clash turned peaceful protests into violent ones.

While both consider Hong Kong a Special Administrative Region of China, the local population still finds it a different country. This allows the people in Hong Kong to have a free press and high levels of trust. However, mainland China does consider Hong Kong a Special Administrative Region of China, and the food supply is often suspect. If you want to enjoy a delicious meal and a relaxing holiday, visit Hong Kong and experience the cultural difference for yourself.

Disagreement with Beijing’s attempts to manipulate feelings

Mainlanders have widespread disaffection with Beijing’s attempts to control Hong Kong politics. Chinese media has made fan club girls’ zeal for the country into a propaganda campaign, and a CCTV editorial said that millions of young people felt pain when the separatists sold out the land. Disagreement with Beijing’s attempts to manipulate the feelings of Hong Kong people continues to grow.

The first significant move in Beijing’s re-entry to Hong Kong was a policy paper declaring that it has comprehensive jurisdiction over the territory. The policy paper also signaled Beijing’s determination to suppress political defiance in the region. Until then, the city could maintain its laws and freedoms. However, China’s offensive accelerated the encroachment of the mainland, and many Hong Kong residents and businesses are worried that it could end the city’s status as Asia’s cosmopolitan capital.

While reports of Hong Kong protests have been widely reported, these stories tend to drown out the quieter mainland voices and may also give chauvinists a giant spotlight. Meanwhile, censorship of state media on the mainland prevents Hong Kong citizens from knowing what’s happening in the city. In addition to reporting the protests, independent media outlets are encouraged to view the story skeptically and avoid putting people into a single category.

As the protests intensified in June, the central Government of China escalated its propaganda and media tactics to control the story. The Chinese Government deployed videos of violent outbreaks in Hong Kong. Protesters defaced the Chinese national flag and emblem, confirming their protests were against Beijing’s claims. And the repressive regime has increasingly eroded Hong Kong’s reputation as a place of free expression.

This unprecedented level of discord has led to an increased inflammatory climate within the city, and some people believe a color revolution could be in the works. However, the NPC Standing Committee, made up of elected members of the Hong Kong community, sought opinions from a wide range of citizens on what kind of democracy should look like. It’s August 31 Decision has prompted widespread disaffection among Hong Kong citizens.

Mistrust of protests in Hong Kong

The dissatisfaction with the Hong Kong government has led to unprecedented protests in Hong Kong, even though the territory enjoys near-full employment and a high GPD per capita. While Hong Kong has generally enjoyed high levels of economic development, wealth inequality is a significant source of discontent. Hong Kong has one of the highest Gini coefficients in the world, with approximately one in four young people living in poverty. The National Security Law, which China imposed on Hong Kong unilaterally, is also a source of concern.

The proposed legislation included provisions to extradite Hong Kong citizens to Mainland China, breaching the principle of «one country, two systems» and causing regional political instability. Pro-democracy figures said this would undermine the wall between Hong Kong courts and the mainland judicial system, and wealthy businesspeople and Hong Kong residents were particularly concerned. The bill has since been tabled, but the issue is far from over.

The Independent Police Complaints Council was set up to investigate complaints against police officers. But the IPCC lacks public confidence in its ability to effectively investigate complaints and enforce the law, as many of its members are appointed by the Government. Moreover, many protesters who experience police violence fail to file complaints about fear of prosecution as rioters. Further, establishing that police abuse occurred requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt, and some videos on the Internet do not have such evidence.

A broader issue is that Beijing’s stance on democratic reform is deeply flawed. Beijing has long desired to maintain the current level of control over Hong Kong and dismantle the bonds of opposition and shared identity. As a result, state media have warned people against using pro-democracy symbols in Hong Kong. But in reality, the aim is to limit protests in Hong Kong to a bare minimum.

Earlier this year, 7,000-strong front-line hospital staff went on a four-day strike to demand the Government close the border with Mainland China. They hoped the wall would be completed to limit the spread of disease. However, the Government’s decision to cancel the elections coincided with the coronavirus outbreak. They hoped to capitalize on an angry public, and the cases have since dropped to single digits. Nevertheless, government opponents question why the elections were canceled at all.

There are several differences between the two particular administrative regions of Hong Kong. Although both are autonomous, the Basic Law specifies a high degree of autonomy regarding the economic, cultural, and political systems. The Hong Kong SAR is located on the Pearl River Delta. The city has a financial and legal system similar to Hong Kong, and Macau follows a similar approach. The political and legal systems are very similar, but there are also some differences.

Hong Kong SAR

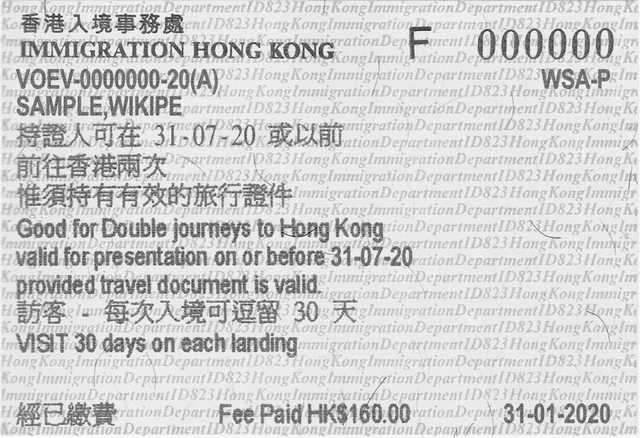

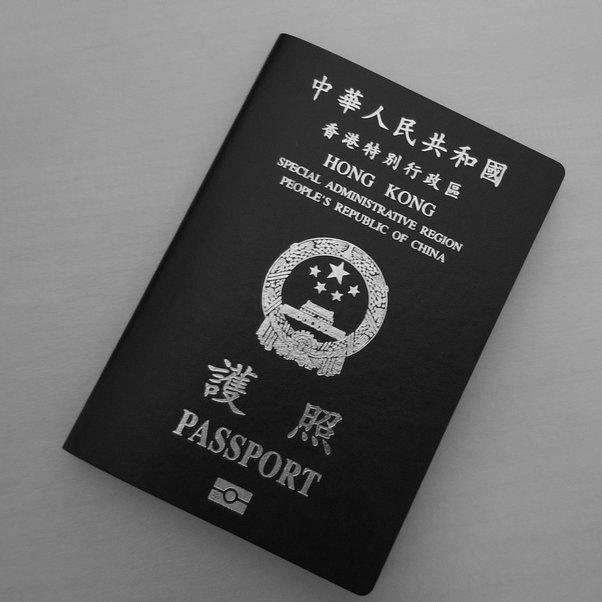

On July 1, 1997, Hongkong SAR (the same as Hongkong) was declared a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). While the CBD is responsible for maintaining the high level of autonomy guaranteed by the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, the transition to PRC sovereignty has raised serious concerns for the CBD. This article explores the problems arising from the change in Hong Kong’s constitutional framework.

Climate in Hongkong SAR is temperate. The average temperature in January is 60 degrees F (16 degrees C), while the hottest month is July. The lowest temperature recorded was 32 degrees F (0°C) in January 1893, while the highest recorded temperature was 97 degrees Fahrenheit in August 1900. Hong Kong receives 88 inches of rainfall a year. Generally, tropical cyclones form over the South China Sea in June and October.

The island’s climate is temperate and humid, with hot summers and cool, dry winters. Hong Kong’s climate is primarily controlled by the atmospheric pressure systems over the neighboring Asian landmass and sea surface. Monsoonal winds in winter blow from the northeast, while warm, wet, southeasterly winds develop in summer. The city also experiences high humidity throughout the year.

Comparative research has its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Comparative studies can help identify societies’ common and distinctive characteristics, institutions, and structures. They can also help develop classifications for social phenomena and determine whether shared causes can explain the differences in their practices. The results of comparative studies are helpful in policy-making, economics, law, and tourism. They provide a unique perspective on two SARs.

Macau SAR

The Macau SAR is part of China. The SAR and the Chinese mainland share a common currency and legal systems but maintain their legal, administrative, and judicial systems. Macau and Hong Kong participate in 41 intergovernmental organizations and have established their own Economic and Commercial Offices, or DECMs, to protect their interests in international trade. They also maintain Consulate-General offices in Hong Kong.

The MMA is the SAR’s de facto central bank, responsible for maintaining the financial system’s stability and managing the island’s foreign assets and currency reserves. Macau has 29 financial institutions, including ten local banks and 19 branches of Hong Kong banks. The city is also home to 11 moneychangers and six exchange counters. Foreign investors can bring capital to Macau and invest it in the SAR’s financial institutions.

The Macau SAR maintains a robust legal system based on the Portuguese model. The Basic Law states that the judicial system remains intact after the transfer of sovereignty. The chief executive appoints all judges. The highest court is the Court of Final Appeal. Macau has a limited security force, but Beijing’s central Government is responsible for its defense. The Government of Macau aims to foster a healthy business environment and maintain a high level of stability.

The political climate in Macau has improved since the reunification of the two cities. The economy has grown exponentially since 2000, driven by a booming gambling industry. Macau now ranks sixth in the world for revenue from gambling, and tourism has skyrocketed from its 1990s low. Major infrastructure projects have been implemented in the region, including a third bridge that opened in 2005. A recent attempt by Macau residents to rally in support of Hong Kong was foiled by the Government.

Legal system in Hong Kong SAR

The Legal system in Hong Kong SAR is based on the common law tradition. During British rule, the law of England applied, but some of its provisions were inapplicable to the island’s circumstances. The legislature modified some of these laws. Today, English and Chinese are the official languages in Hong Kong. The Bodleian Law Library has two series of secondary sources on Hong Kong law, each with slightly different shelfmarks.

The Legislative Council, also known as LegCo, is the legislature of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. It enacts the principal laws of the territory and signs them. They are published in the weekly Government of the HKSAR Gazette in English and Chinese. Supplements are essential legal sources, and sometimes the LegCo delegates lawmaking authority to the executive. Subsidiary laws flesh out the primary rules and are published in Supplement 2 of the Gazette.

The Department of Justice includes five professional divisions, each with its mandates. The Secretary for Justice serves as the chief legal adviser to the Government and is responsible for enforcing the law in HKSAR. Among his other duties, he is responsible for prosecuting all offenses committed in the territory. In addition to the Department of Justice, the Hong Kong SAR has a court system. The court system is based on the common law, which is not adapted to international legal norms.

When researching HK law, it is helpful to know the primary sources. In addition to prior law, the Hong Kong legal system uses case law, legislation, and Chinese customary law. Chinese customary law is also recognized in certain circumstances, such as land inheritance. Chinese customary law is the primary source in certain situations, but this guide will not discuss it. The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Legal History contains an entry on Chinese customary law in Hong Kong.

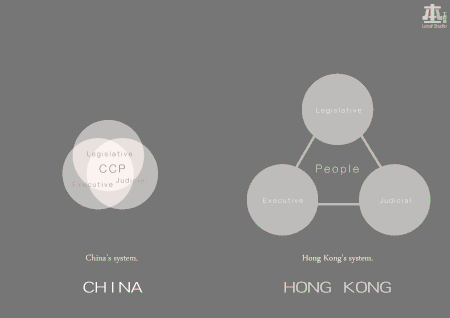

Political system

The political system of HKSAR is a combination of direct and indirect democracy. The significant organs of power include the Legislative Council, the Chief Executive, and the Court of Final Appeal. The Executive Council assists the Chief Executive in making decisions. The Audit Commission Against Corruption is an independent body that functions independently of the Chief Executive. The Department of Finance and Administration consists of different bureaus and divisions.

Compared to mainland China, Hong Kong’s political system is less constrained. Political parties, while not fully entrenched, tend to be relatively new and volatile. In addition, they are aggressive, vigorous, and articulate. They also tend to be autonomous, which allows them to pursue a wide range of political agendas. Although the Central Government governs Hong Kong, political parties are independent in the sense that they are autonomous but are still subject to the rule of the Government.

Pro-democracy legislators vetoed a political reform package on December 21, 2005. Pro-democracy politicians have been openly critical of Bishop Zen and Martin Lee. This has fueled tensions and discontent. While the Chinese mainlanders have a firm grip on Hong Kong, the Government must balance the interests of all the people in the territory. Ultimately, democracy should prevail in the region.

The Basic Law specifies the fundamental rights of Hong Kong SAR residents. It also outlines the Government’s role in regulating the economy and monetary affairs, as well as responsibilities for external affairs. It also specifies the method of interpretation and amendment of the Basic Law. Further, the Basic Law gives the Chief Executive broad powers to make laws for the people’s benefit. Achieving this status provides the HKSAR with a high degree of autonomy.

Influence of Beijing on Hong Kong SAR

The «judicial reforms» imposed by the Chinese Government could have devastating effects on the long-established independence of the Hong Kong SAR. The National Anthem Law, which requires public displays of loyalty to Beijing, and the «fake news» bill, which makes it harder to criticize the Chinese Government peacefully, have eroded the independence of Hong Kong’s judiciary. In response, pro-democracy activists have been lobbying foreign governments for help in their fight for a free Hong Kong. However, the repressive measures could damage the city’s international status as an economic powerhouse and global business hub.

The State Council, 2014, outlines the central Government’s efforts to ensure the HKSAR’s prosperity and development. The document is broken into four sections, the first three framed in terms of central government «support» for the HKSAR’s economic growth. This document also clarifies the mainland’s political and economic benefits in Hong Kong. However, it does not offer concrete examples of how the central Government will use its influence to influence the SAR’s future economic development.

The Hong Kong government has invested in building a vast country park system covering two-fifths of the territory. Many residents in Hong Kong enjoy outdoor recreation in these parks, including hiking, running, and tai chi chuan. Meanwhile, remote areas are used for kite flying and hiking. The Government has also set up well-organized programs to encourage more mainland visitors to visit Hong Kong. There are several reasons why this is so.

In the early 1970s, the Chinese Government sought to limit the freedom of Hong Kong’s citizens by demanding the expulsion of four Legislative Council members. This move struck a blow to Hong Kong’s democratic tradition and signaled Beijing that the «One Country, Two Systems» policy was no longer a permanent reality. As China emerged from decades of isolation, the United States began diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1979.